Interview with Joe Clayton of Pijn

Pijn (pronounced Pine) are an experimental metal project hailing from Manchester, United Kingdom. With an eclectic background of members that includes hardcore, traditional metal, new wave, and influences that combine The Mars Volta, Godspeed You Black Emperor!, and Converge, coupled with a Manchester melancholy, the band is a fresh take on what metal could be. House Vulture was fortunate enough to sit down with founding member and guitarist, Joe Clayton to talk through the bands beginnings and where they are headed next. This was also the first interview I ever gave where I was asked a question by the artist, which I must admit, was pretty special.

Pijn is from Manchester, England. How do you think Manchester has permeated your sound?

The thing people always bring up is Joy Division, New Order, The Smiths, and Oasis, because that’s what everyone associates with the city. And yeah, those are formative bands—great for getting people into guitar-based music. But I feel like for a lot of people they can be both the entry point and the end point.

There’s a big indie scene that’s heavily influenced by The Smiths, but for me, while I enjoyed those bands, I never thought, I want to make music like that. It just didn’t speak to me that way.

There have always been UK bands, though, that I found really inspirational. If we look at Manchester itself, one of my favorite bands was Beecher. They were absolutely amazing. They went to the States to record with Kurt Ballou, got signed to Earache, and played all these incredible shows with bands like Dillinger Escape Plan. Looking back now, it’s wild. Most of them aren’t making music anymore, but one of the guys has gone fully into the kind of metal he loves. He ignored the pressure of having been in a cult-followed band and just did his own thing, which I find really inspiring. I’ve worked with him a lot, and I’m actually working with him again this weekend.

The way that kind of stuff influenced us was more of a long process. A lot of us in Pijn used to play in heavier hardcore or metal bands before moving into something gentler. Back then, we wanted to sound like Beecher, or like Architects in their early days. Then I got introduced to Russian Circles, which opened up a whole new world.

While I was at university in Sheffield, there was also a really strong metal and progressive metal scene. Bands like The Miramar Disaster were hugely influential for me. They sounded like Mastodon mixed with Neurosis—absolutely incredible. And the fact that these were friends and peers of mine doing it made me think, just go for it.

In the UK, we sometimes fall into the trap of being overawed by American bands, because it’s so much easier for them to tour here. You end up seeing them more often than UK bands, so they feel bigger by comparison. But having a few bands in our own scene doing groundbreaking things gave me the confidence to think, yeah, I want to do that too.

You talk about Manchester, and bring up all those bands—Oasis, The Smiths, etc. On your Bandcamp, you’ve got a quote: “positivity entwined with profound melancholy.” A lot of those Manchester bands have this melancholic quality, I’m curious—what that phrase means to you? Does Manchester itself bring a certain kind of melancholy, or is it something more personal?

Yeah, that’s a good question. I mean, especially in the north of England, there’s definitely a kind of dour attitude. It’s that sense of, “everything’s a bit shit, but you just grin and bear it.” And you can feel that in bands like The Smiths. The songs are heartfelt and sad, but the melodies are often upbeat. That contrast really works.

For us, I think it’s less about the city itself and more about personal circumstances. That Bandcamp line came from us trying to capture what the record felt like while we were making it. It was this uphill battle—trying to feel good when you actually feel awful.

There’s a lot of that in UK music in general, I think. It’s not just wallowing in sadness—it’s about pushing through it, trying to climb out of it. And that’s what we’re aiming for as well: acknowledging the heaviness, but also searching for something hopeful in it.

Pijn offers a lot of emotion and passion in the music. Is there a certain moment in your past where you found your passion for music and discovered you were going to make music full time?

I don’t know if there was one single moment, but I’d say it really started at school, around sixteen. That was when I first took a real interest in playing an instrument. I’d had some classical training as a kid—woodwind, orchestral stuff—but I never really felt drawn to it. It wasn’t until my teenage years, discovering bands and new sounds, that I thought, “Maybe I’ll just pick up a cheap bass and start learning as many Rage Against the Machine songs as I can.”

At first, it was just something to do, but when I went off to university, things really began to shift. I ended up in one of those American-style shared rooms, and before moving in, the unit paired me with this random guy. We were chatting beforehand, and I was saying how much I loved Metallica, and he goes, “Well, have you heard of Converge?” I hadn’t. He sent me Jane Doe, and my first thought was, “This guy’s insane—we’re never going to get along.” But it didn’t take long before I was completely converted.

Then, just two doors down from me, there was this guy who happened to be the original bassist for Architects—the one who played on their first record, the really technical one. Seeing how good he was lit a fire under me. I thought, “Right, I need to get my chops up. I want to learn how to play some of these songs he’s written.” He was miles ahead of me—he’d not only written and recorded music, but also taught and performed extensively. That kind of proximity was huge for me, because it pushed me to want to take myself seriously as a musician.

At the same time, he and a few others who’d come up from Brighton were putting me onto all these bands they’d discovered over the last few years. Suddenly, I had this whole new world of music in front of me, and it all just clicked. That was when I realized—I wanted to be in a band. I needed to be in a band. And from there, honestly, it’s been one poor decision after another [laughs].

Is that kind of how Pijn came together? Was that the starting point?

In a way, yeah. Pijn actually started out as just a two-piece—me and my old drummer. We’d gone down to London to visit a friend, and on this long drive we were listening to the first Mars Volta record. We just thought, “This is so good—we need to do something in this vein.” He’d been traveling for a while, I’d come back from some personal stuff, and any projects I’d had before fizzled out. I’d been in a hardcore band a few years earlier that had just fallen apart, so I was really craving something new—an outlet, something I could pour myself into.

On that drive, we were listening to Mars Volta, Godspeed You! Black Emperor, and other records in that space, and it sparked the idea: let’s try something proggy, obtuse, weird—sort of post-rock, but our own take on it. We weren’t entirely sure what it was going to be, but we had access to a studio space, so we just said, “Let’s get in there and see what happens.”

Once we started, it became this process of channeling everything—emotions, experiences, frustrations—into the music. And because it wasn’t like the hardcore or metal bands we’d been in before, it took more work. It wasn’t straightforward riff-writing or verse-chorus-verse stuff. It forced us to think differently, to figure out how to actually do it. That challenge, I think, is what made it exciting, and what eventually grew into Pijn.

You talked about being in these hardcore bands and then kind of shifting into the sound that Pijn has now. But I sometimes find that bands like Pijn and Bossk, can parallel any true metal record. if you put on Desperately Held or From Low Beams of Hope, it just sounds and feels so heavy. With that said, how do you approach writing together as a group?

I think, looking at bands that hit heavy—I love all that stuff. Every now and then, I still think, “I just want to do a nice, easy, really heavy band. There’s a lot of merit in that. There’s a lot of creative stuff, really cool things. But I had more of a connection when I was with bands like that—I saw Godspeed, Russian Circles, Red Sparrows…

Oh, Red Sparrows?

All those… sorry, I didn’t mean to interrupt, but you hit the trifecta of fans I love. I’m so obsessive about Hydrahead and that whole scene… Old Man Gloom… it just hits a different way.

Yeah, exactly. I remember—you brought up Oceanic. I can’t believe I nearly forgot them. They have all these vocals where you can kind of tell what Aaron Turner is shouting, but not really. And I don’t think, at least in the vinyl release I had, there was a lyric insert. It wasn’t a thing that tells you the story. You just have to feel it.

Yeah, exactly. Like from that album Weight—the really long, slow one—they have Maria Christopher of the band 27 doing some vocals as well, and you can’t really tell what she’s saying, but it’s something. And then you get invested. I remember me and this guy from Brighton trying to do a deep dive to find out what the album (Oceanic) was about. It was this weird story of incest and people drowning, this massive thing that I didn’t really get. I attached my own interpretation to it. And I really enjoyed that—having to work at it a bit more.

Yeah. I kind of kick myself because I would really look to a straight-up heavy band. But I just think the way I’m wired; I always want that sense of discovery—the sense of discovery I had with some of those albums.

I wanted to ask about Desperately Held and From Low Beams of Hope. Those EPs feel connected. Desperately Held is more ambient, and From Low Beams of Hope is more direct. Can you talk a little bit about how those came together? How did you get to the point where you thought, “Let’s pull some of these elements and make an ambient record to pair with the more direct one”?

Yeah. Well, initially, From Low Beams of Hope existed in a few different forms over time. The initial plan was for there to be a fifth track—which we have an old version of—and we even snuck parts of it onto a bonus release called Patience & Perspective. The original idea was a four-track album, with a final, more ambient song that took motifs from the four other tracks and created something new.

It was kind of a way to finish the album differently. Initially, the album ended with a big, heavy section, and I didn’t necessarily want it to end that way. So, the idea of an extra track with all these motifs felt like a way to complete the record. But then we ran into limitations with vinyl side length. Adding that fifth track would have pushed it to a double LP, which wasn’t ideal. So, I decided the original version of the album was finished, with that fifth song still hanging in the wings.

Later, when we revisited the album, I wanted to redo a few parts. In doing that, I felt stronger about the four main songs, and we managed to add a couple of small details that resolved the tiny issues that had been holding me back from saying, “Yeah, I can let this go.” It had been a long process—four years or so from when the first bits were written. Some tracks had been played live as early as 2010, and one in 2019. So, I’d been stuck on these songs for years. Re-recording and adding little pieces changed my perspective, and I wanted to expand on what I’d already done.

I’d never been 100% happy with the final track, Desperately Held. I basically scrapped it, tried redoing it, but didn’t like it enough to include it on the album again. So, I decided to take a different approach. By that time, the band lineup had changed quite a lot. Bringing in new influences—like someone working with keys, tape loops, and experimental sounds—shifted the perspective. One member, Tom, works on film soundtracks and ambient solo projects. He introduced me to a bunch of really interesting artists, which also helped me rediscover music I used to listen to years ago, like Alluvium.

So, it was partly about scratching an itch that had been lingering from repeatedly scrapping that track. Maybe I was approaching it the wrong way. Instead of tacking on a fifth track, we decided to rework each song and see what emerged. I had a rough structure in mind for some of them, but I also allowed it to be completely open to what happened when I sat down in the studio with Tom. We tried out a bunch of ideas, had a kind of running list of things to experiment with, and just saw what came out.

Most of it happened in the first day—just reworking the stems from the album, listening to songs I’d been working on for years in a new environment, and experimenting. It was a really collaborative process, just seeing what happened when we played with the tracks.

Earlier today, I was listening to each ambient track alongside the tracks from From Low Beams of Hope and Desperately Held, and it’s amazing to hear how they complement each other.

Yeah, it’s kind of both. It feels like both. It could be an addendum, but it also stands as its own piece. We tried to make it different enough that it would feel like its own thing, but it would still have this tie to the original song, I suppose.

One thing I was obsessed with for a while was that there were two versions of Marching to the Heartbeats by Cult of Luna. There’s the version on the album, and then there’s a piano version they put online for a brief period before taking it down. A couple of weeks ago, someone reminded me of it, and I was like, “Oh my God, I haven’t thought about that in ages.” That stuff, for me as a fan, really makes me want to engage with the rest of the creative process.

When a band gives you two versions of something, it’s not just a different mix—it’s a whole different perspective on the same piece of music. And I really love that. That’s something we want to continue doing.

You talk about Metallica, the Red Hot Chili Peppers… these bands always feel on brand, right? But then Flea, the bass player in the Chili Peppers, is always doing these side projects. Completely different from what the band does. Or Nine Inch Nails, when they put out Ghosts.

There’s something inspiring about seeing musicians, artists, entertainers’ step outside their comfort zone—take something, dismantle it, rebuild it differently, try something completely new.

Yeah, we were sort of influenced by Mars Volta, too.

Flea totally did. I think it was their first record. I remember reading about how they changed their recording process completely—an insane approach. That stuff is really inspiring. Anyone doing something wildly different like that… that’s how you get the creative sparks firing.

I don’t think I’ll ever make someone record their parts to a click track with no idea what the rest of the song sounds like, like some musical genius knows all the puzzle pieces but no one else does until the album drops. I won’t go that far.

Omar Rodriguez Lopez got a similar approach, though. It’s like… a bit like Oblique Strategies. You pick a weird creative prompt to spark something. Reading about a band doing something unusual is a good way to trigger ideas. And it doesn’t have to be good. It just has to exist—put out there into the universe.

Pijn has a very distinct visual aesthetic, the cover art on your records is very angular. Pictures framed in sharp ways, looking through doorways or through some small section of space. Some feel deliberately restricted. Are those choices intentional, or is there a story behind them?

Yeah, no, it’s cool you picked up on that because it really is a big part of it. The artwork is always a huge thing, but it’s also something I personally struggle with whenever it comes time to sort it out. I’ll have ideas but making them happen visually is a whole different skill set. I usually have to lean on other people who are more fluent in that visual language.

Like, with the first EP—I loved that cover. It was a picture taken by my old housemate. There was a really important event that had happened in our lives, something that deeply affected us all, and I wanted to make sure she was included in the project. The photo itself had this weird play of light that resonated with a personal experience I’d had—something disorienting, almost absent, like being unmoored from reality. It felt so representative of where I was personally at the time, so it made sense for the EP.

Then with the first album, it became more about color. We had specific palettes in mind and wanted to draw things together that way. We opened things up to contributions—words, photos, sounds—from people we knew, people who had experienced loss, people who wanted to process it in their own way. We invited creative submissions of any kind and then sifted through everything to figure out how to include them. Some became text, some became voice samples. At one point someone even sent us a full-on noise track—just screaming layered over feedback and distortion—and I ended up chopping that up and weaving it into a song. That whole approach was inspiring, but also really heavy. Sitting through endless recordings of people talking about bereavement and trying to decide what to use—that was tough. Honestly, I don’t think I’d do it again, and I wouldn’t recommend it. It took a toll.

Visually, though, I knew I needed help. I leaned on friends who could provide stronger images and a clearer visual direction, because I was just too immersed in the other parts of the project.

The new album cover is funny, because that picture was never meant to be the final artwork. It started as just a placeholder—something that had the kind of lighting I wanted. I’d been obsessed with this orange-yellow light for years, specifically the glow you get from low-pressure sodium bulbs. They emit light in such a narrow frequency that it completely changes how you see everything. There’s no real color variation—just that yellow bleeding into black. People’s skin tones shift, depth perception changes—it alters your whole perspective. I loved that concept of changing how reality looks and wanted to find a way to bring it into both the stage show and the album art.

At one point we actually hauled a generator out to an abandoned building, set up these sodium lights, and tried to shoot photos. Local kids showed up on bikes and started throwing rocks at the bulbs, asking us what the hell we were doing. It was a chaotic scene. And while I really liked the pictures that came from it, in the end they felt too melodramatic for the record.

The final image actually came from something far simpler. It was just a photo taken outside one of the rooms in my parents’ house. My girlfriend Gemma had found it online somewhere—it had this perfect yellow light spilling out of a doorway, and I thought, That’s it. That’s the feeling. It tied in with everything we were trying to do as a band—using light to literally change how you see the world, mirroring how we were trying to shift our own perspectives personally.

So, I sent it to the designer and said, Something like this—we just need to find a location and recreate it. But then we hit the usual walls: no money, no resources, and I just thought, This is getting ridiculous. The designer finally said, Why not just use this picture? And if everyone else was happy, I wasn’t going to fight it.

As for the colors, the blue on Desperately Held came directly from looking at the color wheel. We wanted something complementary to the yellow of A Hymn of Hope. It was as simple as that—using opposites to tie the two records together.

I love the collaborations you did with Bossk and with Conjurer on Curse These Metal Hands, can you talk about that record, and do you find that collaborations kick off a different creative spark?

Yeah, it does. I really enjoy doing those kinds of projects. With Bossk, we did that one, then we did another with a Russian band on the same label called Anti-Think. Of course, there was the full collaboration with Conjurer. And there have been plenty of other ideas floated around since then, but honestly, the logistics are where it usually falls apart. It’s kind of horrible, actually, trying to get everything lined up.

But when it does happen, those collaborations are really inspiring. You’re forced to either look at your own instrument in a completely new way, or you’re working with new people and adapting to that. Even though I’ve been really good friends with the guys in Conjurer for—what—eight, nine years now, maybe longer, it’s still very different when you actually get in a room and try to make something new together.

You’re used to your own dynamic within your band, right? You know how everyone moves and reacts. Then you add in two or three other people, and suddenly it’s like, “What the hell is this now?” It makes you second-guess yourself. I’ll sit there thinking, I don’t even feel confident in anything I’m doing anymore—I feel like I’ve forgotten how to play guitar. Especially because Dan Nightingale from Conjurer is, hands down, one of the best guitarists I’ve ever seen. And then it’s just me like, “Well, I guess I’ll put on this fancy pedal and do basically nothing.”

But that’s the good part too—it forces you to change things up.

We haven’t done it as much recently, and I think that’s why I’ve been kind of longing for that sort of thing again. I also just haven’t written music in a little while, so the itch is there. But back when we were doing the bulk of those collaborations, we were knocking them out in fairly quick succession, one after the other. And once you get into that rhythm, you’re flexing that creative muscle constantly. Even though each collab is totally different—different people, different sounds—you’re sort of always ready to go. You know what’s happening, and you trust that something will click.

Now, though, I think it would take me a little while to get back into it. I’d feel more inert, a little out of practice.

I think that’s amazing. I’m with you, I like physical media. So, I gravitate toward those things because, for me, it’s always been about the full package. Especially with bands like the ones you mentioned—Pijn, Bossk—I feel like they take all of that into consideration. It’s not just the music, it’s all these other aspects, the tangible and intangible. You’re telling a story through the whole thing. And I think that’s important because I haven’t gotten lyrics from you guys—you have another way to tell that story. It provides another avenue to think about what you’re doing, and not just your story, but how I can project my own meaning onto it too.

Yeah. Cool. Thank you. Do you mind me asking—what do you think the albums are about? Like, what do they mean to you?

So, with Pijn when I sit and listen, it’s different. A lot of times I’ll put on headphones, sit in a dark room, just lay on the couch for an hour and let the whole record play. And your music—it really pulled me back in time.

My mother passed away when I was really little. And for whatever reason, when I was listening—to From Low Beams of Hope—it brought me back to that time. I don’t even know why. Maybe it was the swells in the music, the heaviness that shifts into something ambient and orchestral. It just carried me there.

And I made a note to myself because, honestly, I can only think of a handful of times where a saxophone works in a metal song. Soundgarden had one. There’s that Rivers of Nihil track. The Stooges used sax back in 1970. And then with Pijn—I can’t remember the exact track, they all kind of blend together for me—but the way you used saxophone, it wasn’t forced. It felt natural. It just blended in, subtle but present, and it worked.

That whole record really resonated with me. It brought me back to that place and time. And I think that’s why I gravitated toward it. Not that I don’t love the other records—but From Low Beams of Hope, that one hit me differently. When I listen to Desperately Held, there isn’t a “theme” exactly, but it’s more like a feeling. That’s what I get from it.

And when I talk about feelings and emotions, what I mean is—listening to that music brought me back to the feeling I had when I lost my mother. And then the time after that, not hopelessness exactly, but just searching for a place to land, somewhere to feel comfortable again afterward.

Yeah. That’s exactly it. That’s what we were channeling. For me, it wasn’t my mother, but it was a partner. That kind of bereavement, that kind of magnitude—it’s embedded in everything we do as a band.

When we did Loss, I was actively channeling a lot of that grief. But with the next record, it became more retrospective. Looking back at those feelings, revisiting them from a new angle. The grief is always there, but you can reframe it. You can find moments of positivity in it—like happy memories intertwined with tragedy. It’s deeply upsetting, but if you try, you can shift how you see it. That was the feeling behind the last album—reframing grief through a more positive light.

That makes so much sense. And it definitely connected with me that way. It’s funny you say that, because grief has all these knee-jerk reactions. You look back later and think, What the fuck was I doing? What was I thinking? But that’s part of the process. And when you come out the other side—when you can look back from that new angle—you realize there’s positivity in it too. You’re still feeling it, but you’ve accepted it. You’ve purged a lot of that, and now you can sit with it.

Yeah. That’s great. The messy period, you know? And then kind of just moving through it—it’s not really moving on. It’s more like finding a way to keep going.

I think that’s one of the things I gravitated toward. it just felt very organic. When I think of waves in the ocean, that’s exactly what it’s like—you have this feeling, it swells, it climbs to a kind of climax, and then it naturally comes back down. I just connected with it.

That’s amazing. I’m really glad it connected with you. I feel like what you’re describing—the process you were going through, the way you connected with it—is probably universal. It’s not just you.

What’s next for Pijn?

So, we did quite a bit of touring last year. This year, it’s been more about finding balance. We’re all aware that this will never be a full-time occupation, so it’s about fitting it in sustainably.

We’ve got a short tour around the UK at the end of the year, and a one-off festival in China—which is pretty nuts. We saw a poster on our website the other day. We had no idea it was all confirmed until the visas came through. Then suddenly it was out there. It’s really exciting.

Basically, we’re trying to set a plan for a tour early next year and actively breathe between projects. I definitely put a lot of pressure on myself to keep doing things because in this day and age, if you’re not on TikTok or whatever, people forget about you. Our stuff doesn’t lend itself to that—it’s a slow burn genre.

So, we wanted to take a bit of time to figure out what we want to do next. It’s not about stopping—we’ll see each other more, write more—but without trying to squeeze in a ton of shows. We’ve been doing bits and pieces of writing, but opportunities keep popping up, like the festival in China. It’s amazing, but it takes time, so we can’t dedicate as much to writing as we’d like.

Interview with Mike Lewis of For Love Not Lisa and TenKiller

If anyone were to ask a person of a certain age and musical taste what the coolest movie soundtrack ever in the history of the world was, I would bet money that they would say The Crow Soundtrack. Mike Lewis wrote one of the most underrated songs on that record, “Slip Slide Melting” as part of one of the most underrated bands of that era in For Love Not Lisa. House Vulture had the pleasure of speaking with Mike in an eye opening interview about that time period, his other project, Puller, and the freedom surrounding his newest project, the superb Tenkiller.

You are originally from Oklahoma, can you talk about growing up in Oklahoma City and how it has become a part of your music?

Oklahoma is known for figures like Will Rogers and a lot of country artists, but none of them live there anymore. I lived in a little town outside Oklahoma City, which had this “white flight” vibe. So, of course, I became a punk rock kid because of it—fighting against the man and all. Oklahoma had a really interesting music scene. The Flaming Lips were regarded as the stars of Oklahoma. We all listened to their albums in high school, and they were the only signed band we knew of. From them, many other bands grew up in that culture. There was a band called the Chainsaw Kittens that was on Mammoth Records and made a record with Butch Vig. Two members of that band later became part of For Love Not Lisa.

There was a lot of alternative rock beneath the Flaming Lips, which set the tone for our influences. My influences are kind of strange because I grew up in the church and around youth group kids. On one hand, I was listening to Minor Threat and the Sex Pistols, but on the other hand, I was into the Altar Boys and choir music—Christian rock approved by my parents. All that shaped who we are. I don’t know how that translated into the music, but those are definitely themes from my upbringing.

It was a mix of angry angst rock combined with this weird rebel Jesus narrative. It doesn’t all work or match. My father was a police officer, and my mother was a teacher, so I didn’t get away with much. You can see where my rebellious spirit came from! Eventually, like all things, we had this saying: if you want to be a deep-sea fisherman, you have to leave the shore to fish. We knew that being a real band that was actually going to get a record deal couldn't happen in Oklahoma. The Flaming Lips were the exception. We just didn’t think we could make it that way, so we left Oklahoma and moved to Hermosa Beach, California.

Can talk a little bit about For Love Not Lisa. You went on tour with some bigger-name groups in the 90s.

Yeah, I’d say a couple of things. We had a running joke in our band that if you wanted to become famous, you just had to play with us. We played with everyone. We opened for the Stone Temple Pilots in Santa Monica when they were just starting out—and they blew up. We did some shows with No Doubt in Chicago, before they had a record deal, and they also exploded. Literally, we did two or three shows with Rage Against the Machine right after they came out, and there were only like 50 people at our show. Then they blew up, and we did a string of dates with Green Day during the Dookie album, and then they blew up too. So that was our joke: if you wanted to become famous, just play with For Love Not Lisa, and then you’d make it.

But I’d say that making music is already hard, right? There’s so much saturation in the industry. Everyone’s fighting for airtime and tours, just as they are now. The only thing that could make that worse was either having a drug problem, which we did not have, or making really poor decisions. We basically died at our own hands.

There’s probably a book or a documentary about how a band can screw up their career—more about overthinking and having big ideas. We did it all; we screwed up in almost every way possible. Take an industry that’s already hard to break into, and then complicate it with poor decisions and stupidity. Yeah, we successfully killed our own career.

Interesting. But honestly, none of that shows when I listen to Merge. It’s such a great record.

Well, let me back up a little bit—Information Super Driveway is actually my favorite album out of everything we did. After Merge, we toured a lot, and during that process, you’re kind of writing on the road. As a musician, you always want to bring something new—fans want new songs, and honestly, you get tired of the old ones.

What’s funny is, when we toured, we never played “Slip Slide Melting” live. Crazy, right? That was another way we kind of shot ourselves in the foot. There were these super-dedicated “Crow kids”—hardcore fans who would come out just to hear that song—and we didn’t play it. The truth is, it was tough to perform. Playing it live was really taxing on me since I had to handle both guitar and vocals. Eventually, I just grew to hate playing it.

But looking back, that was stupid. It’s like when a big band refuses to play the one song everyone knows them for. I wouldn’t call it a “hit,” but it was the track people associated with us. Not playing it felt like a slap in the face to the fans.

Anyway, Information Super Driveway marked a big shift for us. We moved away from the loose, jammy, kind of ethereal stuff into tighter, heavier, math-rock-inspired rhythms. At the time, we were listening to bands like Quicksand, Helmet, and Orange 9mm—those heavier, mathy rock sounds.

That’s also when we worked with Stephen Haigler, who had produced Quicksand’s album, plus records by the Pixies and a ton of other great bands. He’s an incredible producer, and working with him was an awesome experience—the complete opposite of making Merge.

Even shared space with Snoop Dogg and Warren G—played basketball with them at night. But by then, we’d burned through label goodwill. They barely supported us, and we had to fund our own video.

The turning point came in Salt Lake City. We showed up, the owner told us zero tickets had sold, handed us our guarantee, and said, “We’re not even opening the bar tonight.” That was it for me. I was done. We broke up, and I moved back to Oklahoma to start Puller.

Do you think it’s easier now to get your music out there because of how the industry has evolved?

With Spotify and streaming, the pressure has lifted a bit. You can do whatever you want, but you also have to do everything yourself — write, produce, promote.

That’s a double-edged sword. It’s still a business. I’ve owned small businesses with my wife, so I know what it takes. It’s authentic, but it’s not always profitable. Getting music out is easier now — my first CD was crazy expensive, and I had to work two summers just to buy CDs for my band. Now, Spotify and digital distribution make it simple.

But what’s missing is promotion. You can release a song, but if no one hears it, what good is that? Everyone can release music now, which is great because it takes power from record labels. But it also means there’s so much music out there, it’s harder to stand out.

Labels don’t sign unknown bands anymore — they wait to see what’s trending and then sign those bands. I prefer it this way because I have full control. No label telling our producer to recut a single or change something. We’re self-funded — I pay out of pocket. I don’t care about sales, but it’d be nice to break even. Everything we do is about the next step.

Social media platforms like TikTok, Instagram, and Facebook help. When I started Instagram, I thought growing followers would be slow, but now we’re close to 6,000 in a year. There’s no viral button, and I’m not a “hot” guy, so my content isn’t going viral, but it’s in my control. We’re connecting with people who like Americana, old country, and rock.

Back in the day, I didn’t know who my fans were or how to reach them. I wasn’t in charge of promoting tours. Now, I can tell people directly about shows and tours. We’re doing a tour of record stores soon — two shows a day, free shows, no barriers. I love that.

It’s like laser-focused marketing: the people who like you find you, and you can communicate with them directly. Bands never owned their audiences before. Maybe some had mailing lists, but that was tough to keep up with. Now, the power is in my hands. I can work as hard or as little as I want.

Sure, sometimes I wish a label would pay for PR or promotion. That sounds great, but then they own your music. I get to keep mine, and the only people I have to please are my bandmates and partner. We have a whole second album written, and we decide if it’s an EP or singles — no label deadlines or rules.

Do you guys ever play anything outside of Tenkiller? You mentioned cover songs—do you ever revisit Puller or For Love Not Lisa in a different way, or is it just moving forward and leaving that behind?

Honestly, I’m done with that. There’s a big ’90s resurgence, and I even talked to a big manager who suggested, “Mike, have you thought about putting Puller or For Love Not Lisa back together? You could package those bands and do a reunion.” But I’m done. I don’t want to be the ’90s rock guy reliving the past, especially since we were never huge anyway.

I mean, yeah, millions of people listened to our music on The Crow soundtrack, but that doesn’t mean they’re fans who’d come see a show. I’ve completely walked away from all that. That was fun, but now it’s about looking forward. This is what I’m doing until it’s done.

(Since we last talked with Mike Lewis, For Love Not Lisa recorded a new version of “Slip Slide Melting” available on Spotify and embedded here)

That’s interesting because I came to you guys through the Crow soundtrack. I got into your music and then bought the Merge record and went through your catalog. The Crow soundtrack was huge—probably one of the top five soundtracks ever. How did that happen?

It’s still going! I mean, it’s amazing. I have a double platinum album on my wall, and it’s already gone triple platinum.

So here’s the thing: that first album has usually been written over four or five years. From the time you start as a garage band, the songs come from different eras, and by the time you record it, some of those songs aren’t necessarily who you are anymore. You've started to morph and change as you tour and play shows, figuring out your identity. We had a real loss of identity—we were writing 13-minute-long songs that had no chance of ever being on the radio.

I mean, Tool can do that, but we were fans of The Cure, and I liked those long, huge intros. So we ended up with a lot of songs that were way too long. During the time we were making decisions as kids from Oklahoma, we picked a producer who later became amazing. I have to say that because I’ve been accused of knocking him, which I’m not—he went on to produce big records and was awesome, just not with ours.

But we were starstruck by him. He was in the band with Perry Farrell from Porno for Pyros, and when we started recording, it was super hard. We recorded it at Crystal Studios in Los Angeles, where artists like Michael Jackson and many Motown bands recorded. They had a one-of-a-kind board—only one engineer knew how to work it. From the beginning, everything about this album was complicated.

Two weeks before recording, we fired our drummer and had to bring in a friend, Aaron Preston from Oklahoma, who had to learn all the songs in two weeks. There was no time to gel as a band. Midway through the album, we replaced our bass player. So, that album was six or seven weeks of torture, and many times it felt overwhelming.

When you listen to that album, there are a couple of good songs, but I think it’s lost in production. It’s hard to listen to because it feels like a band that tried too hard, and a lot of the songs weren’t reflective of who we were anymore. Through that process, we ended up with a totally different sound.

I’ll even add this story: the label gave us an art director to design the album, and I wasn’t happy with what he was doing. So, I said I would design it myself. I had no design experience, but I bought a $10,000 Apple computer—very expensive at the time—and figured it out. We found an incredible photographer who did some very provocative art. Pantera later used one of his artworks for their album cover.

We picked a provocative photo for our album—Perry Farrell had also used a striking photo for theirs. We made an image that couldn’t be shown without being darkened. It was a double image of a woman touching herself over a pig placenta. It lost a lot in the album art, so that was another misstep we made.

Then, Silvia Roan, the head of the label, called and said, “Put my band on ‘The Crow’ soundtrack.” So, that’s how we ended up there. We were probably the least famous band on it, and at the time, I didn’t know much about the comic. Once we saw the trailer for the movie, we realized its potential and how dark and cool it was.

We quickly made a music video for the movie, cutting the song down to fit it into the format for MTV. We were lucky to use footage from the film. We spent so much time on that video that by the time it came out, the interest from “The Crow” had waned, and we did not get the airplay we could have if we had acted faster.

Puller had a good run too. And now you’ve got Tenkiller, which has a different sound—punk roots but with country and Americana touches.

After Puller, I was broke, divorced, homeless. My car got repossessed. I put my guitar away and went into business to survive. For years, I didn’t play at all—still loved music, but I was burned out. I’ve always had wide tastes—punk, metal, singer-songwriters like Ryan Adams, Americana. Over time, Tenkiller just grew naturally from that mix.

So, I was in the business field, and I’ve been listening to music the whole time. I was always on the music business side, then I moved into the outdoor space, doing marketing — that’s what I do for a living. Eventually, my mom passed away last year.

And suddenly, I’m hearing songs again. I have this theory that when you’re younger, you have all this angst, anger, and pain, right? But as you get older, get married, and find happiness, that angst and anger kind of fades. So I’d ask myself, what do I write about now? Little League soccer? What do I sing about?

When my mom died, it brought the hurt back into my heart, and I started hearing songs again. So I called my friend Clint (McBay)— he played bass in For Love Not Lisa. He was the go-to guy whenever I needed someone to tour with. We’ve stayed friends all these years, and now he’s also a guitar player. I said, let’s write some music together, and he just jumped in.

One of my regrets is that my poor mom had to come to all those heavy punk and metal shows I played in. She hated the music, but she never said it. She was sweet and supportive — a little schoolteacher lady — but I just knew it was rough for her. She’d come to a show where I’d be screaming, the crowd’s moshing, and that was her experience supporting me.

Now, in my “old age,” I listen to a lot of singer-songwriters, people like Tyler Childers, really into the new Americana and country scene — all these cool artists. I thought if I ever did music again, I wanted it to be completely different from my past. No more alternative rock or heavy music. I wanted a totally different direction.

Before, when we wrote songs, we were constantly editing ourselves. If something sounded too poppy, we’d make it dissonant, heavy, and chunky. If a melody popped up, we’d run the other way — back to Fugazi or something. So we never wrote catchy songs on purpose, because we were trying to fit a certain scene.

Now, with this new project, I’m writing everything. We’re writing Southern rock, some twangy, bluegrassy stuff — there’s even a track on the new album that’s a full-on old-school bluegrass song, and I’m playing mandolin. This time, I wanted no rules. No pressure to fit a genre or sound a certain way. If it’s a good song and we like it, it’s in.

Sometimes, I’m playing acoustic guitar, then we finish the set with my old Gibson Les Paul and heavier songs. I’m just having a great time. This music is very different from everything I’ve done before. With For Love Not Lisa and Puller, we had to be booked in very specific places for very specific crowds and tours.

With this band, Tenkiller, we can walk into a bar in downtown Nashville or a brewery, and people of all ages and tastes dig it — heavier songs, softer songs. It’s got a wider appeal, more melodic, and every song so far has had three-part harmonies, which never would have happened before. I’m just leaning into it, having fun, and I think this is the best music I’ve ever written.

Sometimes I think about how I had to start over — relearn guitar and singing after 20-plus years off. I remember having a publishing deal and a record deal, and I wasted a lot of that stuff. But now, it really comes in handy.

The newest Tenkiller record “Burn the Boats” came out August 1st? And you have a whole second album written already?

Yeah, it’s been funny because in the past I thought way too big and planned too far ahead. This time, I’m focused on small, achievable goals — check one off, then move on.

Last year, the goal was just to write songs and play live. At our first shows, we played three originals and a bunch of covers. We didn’t even know what kind of band we were — Travis Tritt, The Clash covers, all over the place.

But I promised myself and the band I wouldn’t waste their time or make them play to empty rooms. Everyone’s got families, kids, and three of our guys have special needs kids. Sometimes their families come to the shows — it’s a real family vibe, which would’ve been taboo back in the day.

So we set short goals. I wanted to play a local copy shop owned by a country singer — check. Played an outdoor festival at Jack Daniels — check. Wanted to make a Christmas song — check. The plan is to keep moving forward, one step at a time.

And I want to say, we’re just making these little goals as we go along. The big goal has always been to make an album—my first album back. What we’re doing now, is a waterfall schedule: releasing a new song every six weeks until we put the whole album out. So after six singles released over six weeks, it’s time for the album release.

That’s been the goal—put out an album. In my whole career, back in the ’90s, vinyl wasn’t cool. CDs were ruling, and cassettes were gone. So I never had a final album on vinyl. This vinyl resurgence means this is my first vinyl album, and that was a huge goal for me. We could release digitally or whatever, but I wanted a final album—a physical record that goes into a record store.

We actually spent more time on the vinyl packaging than anything else. Some people don’t buy records at all, but I wanted to make something for collectors. We spent way too much money on it. It has all these extras. We hired this guy, Tyler Hackett, a woodcut poster artist from Utah. He created the album cover and a limited-edition woodblock-printed poster that comes with the album. We made this for collectors, for someone to really care about it.

Even the vinyl colors are special: the first run is one splatter color, so the next run will be a different color. So someday when I’m gone, if anyone cares, they can say, “Do you have the blue one or the red one?” We made this as art for a very specific collector. It might be a small group, but it was worth it.

I’m excited because I never had a final album before. It might sound silly, but it’s not. The vinyl and even cassettes are making a comeback, which is wild. People still listen to CDs, too. The biggest controversy was when we opened pre-orders a couple weeks ago and got comments like, “No CD version? What?!” I didn’t think people still cared about CDs. I have some, but mostly for show.

We ended up adding a CD version and had to redo some of the artwork to fit the CD format. It was a surprise to me that people still want CDs. It’s crazy but cool.

Whats next for you and Tenkiller?

Yeah, we’re doing record store runs. I don’t know exactly where yet, but multiple record stores reached out to us, which was surprising. I thought we’d just put the album in a few local stores, but lots of stores want to carry it.

Honestly, I don’t know if we made enough copies. When we made it, I thought these might just sit in my garage forever. So it’s a weird twist that stores want to carry it.

My new theory is, instead of trying to play clubs and convince people to pay $15 and show up, I’m just going to play record stores. If we can do two shows a day, early enough, people can still go out later. I’d rather sell albums and play shows than chase club guarantees.

Interview with Donita Sparks of L7

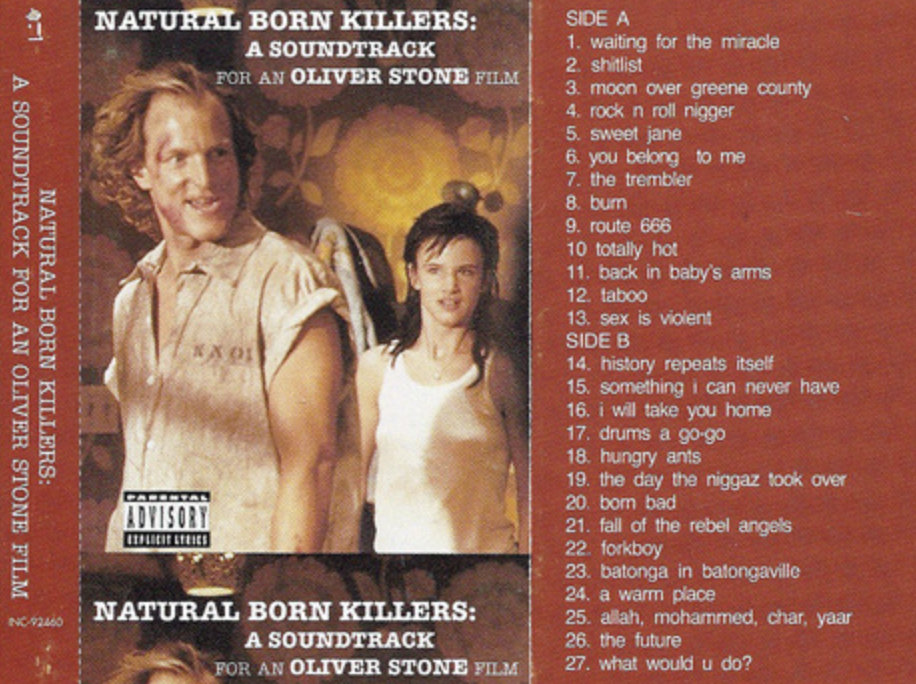

If you are a fan of L7, like I am, you know exactly where you were when you first heard them. For me, it was in high school, in my friends basement, with various substances involved and One More Thing blasting on cassette. Or, the near perfect scene in Natural Born Killers where Mickey and Mallory Knox beat the shit out of some local cowboys in a bar with Shitlist cranked. Or the video for Pretend We’re Dead in heavy rotation on MTV, when it was actually watchable. Doesn’t matter where you were, L7 is the epitome of punk, with Donita Sparks as the engine. House Vulture was able to spend some time talking with Donita Sparks with topics ranging from that violent scene in Natural Born Killers, to her love of the Ramones and Suicidal Tendencies, to the upcoming 40th anniversary shows in LA.

What was the transition like from growing up in a Midwest town to moving to L.A. How did that shift influence your path, especially in terms of meeting L7 and how the band came together?

Well, I grew up in a suburb of Chicago, but I was very connected to the city. My parents worked downtown, I worked downtown—I was a foot messenger after I graduated high school, just trying to save up money to move to L.A.

I used to go into the city all the time, whether it was for concerts or to go dancing at clubs. So even though I was technically a suburbanite, I strongly identified with being from Chicago.

That said, I really didn’t like the weather in Chicago. I had these big, kind of vague aspirations—just a general desire to do something in the arts. I didn’t want to go to college like my parents hoped I would, so I thought, Okay, the best thing to do is just move.

I was really drawn to the fantasy of living in Los Angeles—and honestly, a lot of that fantasy turned out to be true. So, I chose L.A., and I’m really glad I did.

I know you were involved in the LA punk scene, but how did you meet Suzi Gardner and Jennifer Finch to form L7

Suzi and I, at different times, worked at L.A. Weekly, which was kind of like the Village Voice of L.A. We were more in the art-punk scene, I would say. We knew a lot of people—writers, artists, musicians—just a very creative circle.

It was actually a really cool place to work because it truly was a cultural hub, and there aren't many of those in L.A. You're usually either in the film and TV world—that's a whole community of its own—or you're in the music scene. But at L.A. Weekly, we got exposure to a mix of all of that.

Suzi and I were each in different bands at the time, but she had a tape with a couple songs she was working on, and I really loved them. So we decided to start a band together.

It took a while to find the right people. We went through quite a few other members before eventually connecting with Jennifer—and later on, Dee (Plakas) joined us on drums.

I had the Smell the Magic T-shirt, and I was the only one at my school who had it. I wore it all the time, and no one really got the joke... until the Latin teacher kicked me out and made me turn it inside out.

I’ve always considered L7 to be a punk band. You came up during that early ’90s sea change in music. I wanted to ask about that moment in time—what was it like to come up through that shift in music? Did it feel like a natural progression in music or did you notice that the scene was changing?

Yeah, you know, coming out of the ’80s, there was definitely a polished, MTV-driven kind of vibe. Even bands that started out rough around the edges eventually got more groomed—more polished, danceable, slick. Neon colors, big hair, that whole thing. And that was fine! Nothing wrong with that.

But by the late ’80s, things were shifting. Suzi and I started in ’85, and we saw ourselves as punks doing a stripped-down metal—or hard rock—sound. No long solos or technical wizardry. We weren’t even good enough to play those kinds of solos even if we wanted to, but honestly, we didn’t like them. We didn’t care for those long-winded, winking solos. We wanted something more primal.

We were really into the slow, moshy stuff. Like, we loved Suicidal Tendencies—but especially their slower, mid-tempo grooves. Not so much the fast parts, but those dark, heavy rhythms. That’s what we were drawn to. So our early stuff definitely had that kind of vibe, and honestly, we still love that dark groove.

That’s kind of where we started from. And then as time went on, we started to open up more to our pop side. I think we’ve gone through some changes—but cool changes. I’d say we became a better band later on than we were early on. But of course, some fans would say the opposite. Who the fuck knows, right?

What I do know is that when we came out, we looked and sounded very different from what was going on in the L.A. scene at the time. We had no idea that something kind of similar was happening in Seattle and New York. But we had our own recipe—our own sound and style.

L7 founded the Rock for Choice concerts, a benefit concert supporting and raising money for abortion rights. Would you talk through the impetus behind it, and what kind of lasting impact you think it had? Do you ever see it coming back?

I don’t think we’ll bring it back—and really, anyone can if they want to. The copyright actually belongs to the Feminist Majority Foundation in L.A. We handed that over to them pretty early on.

Back in 1991, abortion rights were seriously under attack. Bush Sr. was still president—Clinton hadn’t come in yet—and it was a scary time. Clinics were being bombed. It felt like things were unraveling, and no one in the music world was really doing anything about it.

We were young women, and this issue was personal. It felt like something we could do, something that was in our wheelhouse. We had grown up going to concerts like Rock Against Racism. We’d already done benefits for Greenpeace, helped fund a schoolhouse in Nicaragua—stuff like that. So we thought: Why not a pro-choice benefit? No one else was doing it.

So that’s what we did—and it was really successful. Bands gave their time, their energy, their voices. Pretty much every major band from that era played a Rock for Choice benefit at some point.

It raised hundreds of thousands of dollars—funds that went toward legal fees for clinics, security systems, surveillance equipment, and other critical support. So yeah, I think it had a big fucking impact. We’re really proud of that. It was pretty fucking awesome.

The song Shitlist is probably in my top five favorite songs of all time. I know it's one of your more popular tracks, but I absolutely love it.

I wanted to ask you about its use in Natural Born Killers. I’m sure you’ve been asked before, but I thought it was used really powerfully. I’d love to hear your thoughts on how it was used—especially since you wrote the song.

I’d say... I don’t like violence, so I didn’t love it very much, to be honest.

But—I loved Juliette Lewis’s performance in that scene. I thought she was fucking incredible. She just owned it.

Personally, though, I’m not into violence. I’ve never even been in a physical altercation with anyone. It’s just not who I am. I’m not the kind of person to get in your face or throw down.

And I think a lot of people have this impression that L7 is like that—super aggressive, confrontational—but we’re actually not. We’re mostly peaceniks.

That said, when you write a song like Shit List, it lets you get those frustrations out. You might be furious, insulted, fed up—like you just want to scream in someone’s face. But instead of doing that, you put it in a song. That’s how you process it.

Exactly—channeling that rage into something artistic.

Totally. And I love that people love that scene. I love that it introduced so many people to L7 and to that song. So yeah, I’m totally cool with it.

It’s interesting—you talk about being a nonviolent band, but that movie (Natural Born Killers) is kind of the epitome of violence.

I know, right? It is interesting.

And it was... man, it was something we really thought about. We actually pondered whether we should even be a part of it.

We read the script, and it was like—whoa, okay. It was intense. And sometimes, when you're reading a script, it’s hard to tell: Is this a commentary on violence, or is it just violent?

Oliver Stone meant it as a commentary—on a violent society, on the way the media glorifies violent criminals. That was the intent, I think.

But still, it was violent. No matter what the message is supposed to be, it’s a very violent movie.

Reading that script, it was like, “Jeez... do we want to be involved in this?” It definitely gave us pause.

But people really dig that film. And yeah, at the end of the day, it is a commentary. It’s just... heavy.

Another one of my favorite songs is Talk Box. Can you talk a little bit about what inspired that song, or the story behind it, if there is one?

Oh, interesting! I'm glad you like that one. It doesn't get a whole lot of fanfare, but—cool, that's great to hear.

Yeah... there is a story behind it, but it's kind of dark and depressing.

I think the song itself sort of conjures up its own imagery. You can feel that when you listen to it—it paints this moody picture.

When you're writing a song, there are usually a lot of things happening at once in your head. It might be an image, or a feeling, or a moment—sometimes even something someone told you. It becomes this mix of experiences. Some things are autobiographical, some are not.

It could be something you read, something you overheard, or just a combination of weird little pieces that your brain puts together like a collage.

I like that Talk Box is evocative in that way—it lets people pull their own meaning from it.

And I also just really liked that I got to use an actual talk box on it—which is this super peculiar little gizmo. We used to play it live, too. Jennifer wants to bring it back! But honestly, it’s kind of a pain in the ass.

You have to use this rubber hose that comes out of the talk box. And while you're playing guitar, you kind of "talk" into it.

You have to strap it to the mic stand, and it looks so weird—like some medical apparatus. It looks like a tracheotomy.

Also, I’ll say this: the title Talk Box works on a few levels. There’s the guitar pedal—the literal talk box. But also, like a telephone—it’s box-shaped, and it’s where people leave messages, have conversations. It all kind of ties in.

L7 broke our collective hearts when you went on hiatus. What ultimately brought the band back together?

Yeah, totally. We went on hiatus because Suzi left the band. And at that point, the wheels had just completely fallen off.

We had no manager, no record label, no money. It was just Dee and me—and no support system at all.

We didn’t even have a full band anymore. All we really had was a website and our fans. That was it.

And we just didn’t have the energy at that point to start over again—like, find a new guitarist, new bass player, rebuild a team. We were worn out. So we decided to go on an indefinite hiatus.

I very specifically didn’t call it a breakup—because I knew if we officially broke up, there was no way in hell we’d ever reunite. I didn’t want to be that band.

So calling it a hiatus gave us an out.

Then, years later, a lot of our peers started reuniting, and we were like, "Well, if we’re ever gonna do this—if we’re gonna take some kind of victory lap—we should do it now."

Because if we waited longer, we’d be older, and it’d be harder to pull off.

So we got back together. And now we’ve been on this reunion jag for, like, ten years—which is kind of wild, but awesome.

We released Scatter the Rats, which we really liked. We’ve put out a few singles since then, too.

And I’m proud that some of that newer music still has something to say.

Like Cooler Than Mars—that song’s about billionaire assholes going into space just to stroke their egos.

And I Came Back to Bitch is basically calling out greedy Wall Street dudes trying to claim rock star status or whatever.

So, yeah, I feel like we still have something to say. And that feels good.

I think you’ve built this incredibly solid fan base, once someone becomes an L7 fan—once they get it—that’s it once it grabs you in the gut and pulls you in, there’s no going back. You become a fan for life.

Totally. Especially with bands that maybe weren’t massive, chart-topping acts. Like, I’m a Ramones fan—forever. And that loyalty runs deep, especially when the band didn’t sell billions of records.

Exactly! It’s like your loyalty almost becomes stronger because of that. Like, you know they should’ve sold millions, and because they didn’t, you feel even more connected. You’re in the fight with them.

Yeah, I think so. And don’t get me wrong—selling a lot of records doesn’t automatically mean a band sold out. I mean, the Rolling Stones sold millions, the Beatles sold millions—I don’t think of them as sellouts at all. But when you're a fan of a band that didn’t get that level of mainstream success—when you feel like they deserved so much more—it just intensifies that loyalty. Like, for me growing up, the Ramones were everything. And meanwhile, the biggest sellers at the time were bands like Journey, and I just didn’t connect with that at all.

It felt like I was fighting for the underground, you know?

Are there any current bands that you are listening to that still inspire you?

Yes, there are several bands out there that I think are incredible. Amyl and the Sniffers are one of them. She’s an amazing front person, definitely one of the best I’ve ever seen. Not too many people know about them yet, but they’re Australian and gaining some recognition.

Another band I like is Surfboard, based in LA but originally from Brooklyn. Their front person, Danny Miller, is also fantastic.

I usually discover new music by hearing a song on the radio and then buying it on iTunes. I find that old school, but I don’t trust Spotify to create playlists for me. Just because I like one artist doesn’t mean I’ll like another, you know? It tends to push me towards either similar female artists or grunge bands like L7. Just because I like L7 doesn’t mean I’ll like every band they suggest.

I’m very much a song person. If I enjoy an album on iTunes, I’ll check out some of the other songs. There’s another band I like called Wooden Ships from Portland—they have a cool, dark ambient rock sound.

In my house, I usually have NPR on all day. They have some great music programs, and occasionally I’ll hear songs that resonate with me. That’s pretty much what I listen to.

L7 are performing some 40th anniversary shows later in 2025, is there anything else coming up for L7, any tours or new music?

Yes, we have a couple of shows coming up. We're playing at Motor Blot in Chicago and a couple of other festivals—one in Orange County and another in Washington state. Then, we’ll have our fortieth anniversary bash in LA this October.

As for next year, we're planning to tour, and we’ll likely release a couple of singles this year. However, we’re not in a financial position to make a full album right now. You know how it is. Plus, Susie's living out of state, which makes things a bit more complicated.

We just returned from Miami, where we got off an amazing cruise with a fantastic lineup of bands. It was such a great experience!

Interview with Tim Perry of Ages and Ages

Tim Perry is the mastermind behind Ages and Ages, a sonic gut punch hailing from Portland, Oregon. House Vulture was able to sit down with Perry and discuss growing up in the Northwest, having his music used by Westboro Baptist Church, and 2010s clouded, and sometimes misguided, optimism.

You were originally from Seattle and moved to Portland. Can you talk about the city and how it influences your music? I'm sure being from the Pacific Northwest has some stereotypes that come along with it.

I mean, probably in ways I don't even know. I've done a lot of traveling—before music even—and had a chance to experience the rest of the country, just kind of bouncing around. And I realized, when I was about 20, that the Northwest was still the place that made the most sense to me. Which was kind of surprising, because we all have that feeling, like, “Well, there’s probably something better out there.” But I just realized, being outside of it, how much I actually liked it.

I like... there's a lot of stuff cooked into the culture of the Northwest that—even though things are changing really fast—it’s still kind of baked in.

And it’s this sense of being off the radar. Like, people aren’t really paying attention to us out here. Even when grunge had its moment, it felt like the media went, “Well, that was fun,” and then moved on. Like, “Okay, cool—back to not paying attention to the Northwest.”

And you still see that now. Like, if you're watching a Seahawks game or something, when it cuts to commercial, they’ll throw on Pearl Jam or whatever—a '90s hit—and it's like, yeah, we’re still living in that.

So yeah, culturally, there's this communal thing that’s been able to, I don’t know... ferment and marinate—or whatever cooking metaphor you wanna use.

It’s also, I think, partly because until recently, there wasn't this huge influx of people or tourism. There was a lot of authenticity. It felt like if you were here, you were here for a reason.

But even back in the mid-to-late ’80s in Seattle, I remember there were a lot of Californians moving up, and that was a big thing. Housing prices shot up. Then in the early ’90s, you had Microsoft, Starbucks, grunge—it all hit at once.

That’s around the time I moved to Portland. Seattle was getting too expensive, especially for a kid just starting out. I wanted to live in the city, be around artists, and make stuff. I wasn’t thinking about making money or becoming successful in some conventional sense. I just wanted to create.

Is it kind of slowing back down to where things are starting to crust over a little bit?

No. I mean, in Seattle, you’ve got Amazon—like, it’s wild there now. It’s not slowing down. Sure, it still has the things: it’s on the Puget Sound, it’s near the Olympics, the Cascades, all that—other stuff I don’t even wanna mention.

But yeah, I’ve tried to look at it from a realistic place. The reality is things change. That whole idea of, like, “this was the perfect moment in time, don’t touch it, seal it in a glass case”—I’m not a fan of that mindset either. I get that things evolve. And I’m at peace with that.

It’s just that, essentially, what I’m seeing is what everyone’s seeing everywhere: a continuing commodification of every microcosmic thing that can possibly be turned into content, glamorized, and sold—or sold back to us.

You go through Seattle—or Portland, even more so—and you’re seeing a product that was sold to people. With Portland, especially, it was like: “Here’s Portland.” But nobody used to care. The most common question I’d get on tour when I said I was from Portland was, “Portland, Oregon? Or Portland, Maine?”

Then suddenly, after a while, it became, “So do you really ask where the chickens come from?”—that whole thing. And it's something we’ve never quite lived down.

You saw this wave of people moving here for that experience. And of course, they bought out the affordable, authentic part of it. And I think, if you’re not from here, you might still see some things and be like, “Wow, this place has a vibe,” or whatever.

But the difference is—it’s not whether the energy is there or not—it’s that it’s been commodified. It’s been turned into a brand. And that changes the energy entirely.

When you take something natural and dress it up, polish it, try to dignify it or whatever—it just doesn’t feel the same. It’s different from something that just happens.

Do you follow any consistent songwriting style, method, or philosophy when you write?

Well, it depends on what you mean by "style," right? If you're talking about some formula—like, first the bassline, then the hook, then the lyrics—I mean, that’s bullshit. I don’t think anyone really writes like that, at least not in any meaningful way.

That said, I have written songs where it kind of just came out all at once. Not like, three minutes, but close—where I sit down, and by the time I stand up, the whole thing is there. And that’s rare, but it’s happened. Usually for me, though, it starts with a melody. That’s always the first thing to show up. I’ll get the chords, the melody, even the structure—verse, chorus, bridge—but the lyrics always come later, and honestly, that’s the part I labor over the most.

Lyrics are brutal. There are a million ways to sound like an idiot. Especially if you're writing about something like gentrification—it’s easy to just say, “People are moving in, rents are rising,” and sound like you’re reading from a bad pamphlet. The challenge is to say something real, but in a creative way. Something that paints a picture without beating people over the head. I’m not trying to be a politician on a soapbox. It’s a delicate balance, and one I think about a lot.

Was there a defining or inspirational moment in your life where you knew that you were going to be an artist or a musician?

Well, for me, when it became specifically about music, I was actually a bit older—I wasn’t a kid. I was around 19 or 20. And honestly, it was just going to shows.

At the time, Modest Mouse was this four-piece band. They’d maybe put out one record, maybe a couple of EPs. And I knew some people who were connected to them—not like, “Oh, I was part of the scene” or anything like that, just, you know, we were all kids. Like my friend Marty, who moved down here and worked with Eric Judy at this awful fast food joint called Dolliver’s. Stuff like that.

And seeing that combination of things... it wasn’t like I’m name-dropping or trying to say “I was there, man”—it’s more that I felt there. Like, I was witnessing something real happening in real time. I was going to these shows, being in those spaces.

My first real show after turning 21—like, bar-legal—was a Modest Mouse show at Moe’s in Seattle (which is called Neumos now). It was a Monday night, maybe 15 people there. And to watch that grow... seeing them go from playing in basements to bigger rooms... that was huge.

And this was all before a lot of things. There was this feeling I’d never experienced before—this energy, this flow. Where the music was affecting the culture, and the culture was feeding back into the music. There was this relationship between it all. And being swept up in that—it wasn’t like, “I want to be famous,” or “I want to make this happen.”

It was more like: This is a sense of community I’ve never felt before. This is closer to truth than anything I’ve known. And I just wanted to be a part of it somehow.

Again, not about fame—just about creating. Being around people who make things, people with ideas. That was really cool.

And then watching Modest Mouse go from those small shows to, like, a couple hundred people. Then seeing them at these weird little festivals—still kind of small—and then all of a sudden they’re playing shows with like 500 people. Watching that growth was amazing.

But then... there was this weird shift.

Around the time they started getting bigger crowds—like, 300 to 500 people—I started noticing these shirtless dudes showing up in the front. Moshers. But not like punk or hardcore moshing—more like this aggro, bro-y kind of mashing. Like, they were just there to flail their arms around and dominate the space. They’d be yelling for “Doin’ the Cockroach,” just trying to start chaos. It made the environment kind of uncomfortable.

And that was strange too, because I remember thinking, This isn’t what this band is about. This isn’t what drew me in.

Isn't it weird to watch how things happen that are beyond your control?

Yeah. I mean, that’s just it, right? Like, you might start out thinking you know who you’re trying to reach—or what kind of audience you’re speaking to—but once things get more attention, more exposure, more fame... that all starts to shift. You don’t get to control who hears it anymore.

We actually had a song that was, I guess, usurped—thankfully in a way that didn’t draw a lot of attention, and we definitely didn’t want to give it more by, like, making a public statement or telling them to take it down. But it got used by the Westboro Baptist Church in one of their Instagram stories.

Of course, they co-opted it in a way we didn’t agree with. It wasn’t the worst thing they’ve ever done—because they’ve done some truly horrible shit—but it was enough that we were like, “We don’t want anything to do with these people.”

But I also knew better than to say anything publicly. That’s exactly what they want—attention. They feed on that. So I just kept quiet. Someone else actually had to tell me about it: “Hey, did you know…?”

And that’s the thing. Once you put something out into the world, it’s not really yours anymore.

But even with all that... at the heart of it, there is something kind of meaningful about it too, you know? Like, to know that something you created—something personal—can reach people, even people you don’t know, and touch them in some way... That’s kind of an honor.

I wouldn’t say that’s the point of making music or making art, but it’s definitely the reason you put it out there. Because if someone claims that doesn’t matter to them—that connection—I’ve never really believed that. Because otherwise, why go through all of this?

There’s a lot about making and releasing music that isn’t easy—or even healthy. Stuff you wouldn’t put yourself through unless you really cared about that connection with people.

So yeah, it feels good to know your work is landing somewhere. But then there’s the dark side too—like how it can be used in ways you never intended.

Another example: one of our songs ended up on President Obama’s reelection campaign playlist. And they didn’t ask us. No permission, no heads-up. We found out like everyone else.

Luckily, I wanted him to win. I didn’t want Romney to be president, so I was down with it. I felt flattered, honestly. I definitely didn’t call anyone up and say, “Hey, take us off that playlist.”

But still—part of me was conflicted. Because I was also disappointed in some of the things his administration was doing at the time—drones, climate inaction, things like that. So there’s that tension: being grateful for the platform, but still wrestling with what it represents.

I mean, what would’ve happened if, like, Puff Daddy had said ten years ago, “Man, this band Ages and Ages is great”? We probably would’ve freaked out. Like, what? How did we get here? It’s a strange world.

Ages and Ages formed following the dissolution of PseudoSix—how did that transition happen?

Yeah, I mean, “dissolution” sounds kind of dramatic—but it really just means something wasn’t working out. And how many times in our lives do we keep trying at something, banging our heads against a wall, and it just doesn’t pan out? That’s what happened.

Playing in a band is like being in a web of little relationships. Everyone's got a different personality, different needs. And when you’re the person trying to steer the ship—making the calls, planning the tours, coordinating the vision—it’s a lot. You’re managing all these dynamics, and they’re managing yours too.

At that time, I was working with some great musicians in Portland—friends, really—but they were also ringers, people with other projects, other commitments. So even when things started moving a little, the momentum would stall. Nothing really happened with it.

Eventually, I kind of quit for a while. I needed space to figure out that weird middle ground between making music and sharing music—like, finding some real way to connect what I was creating to strangers out there in places like Cleveland or Florida. I had to ask myself: Why am I doing this? What’s the point?

It was kind of like going through a breakup. Really hard. But also necessary.

At the same time, I was going through this shift in how I thought about music. I’d come to it relatively late in life, and even though I grew up around Portland and Seattle, I always felt a little alien, like I didn’t quite fit into any one scene. I’d spent a lot of time being overly self-aware—trying to be “cool” or whatever that meant. But eventually, I just let go of that.

I started leaning into this kind of unapologetic enthusiasm—just making music because it felt good, because it meant something to me. I didn’t care if it looked good, or sounded “cool.” It was liberating.

And this was also happening near the end of the George W. Bush era, so there was this sort of emotional backdrop: this weird desire to imagine an alternate universe where people were just out in the woods, living off the grid, creating their own joy, making music like some kind of cultish little community. Like praise music—but not for religion, more like for their own way of being.

But even then, I knew that kind of utopia can’t last. Every relationship, even the best one, has an arc. Everything that grows is also going to decay. So yeah, there was all this angry optimism in the music—this real desire for joy and connection—but also an awareness that it would all inevitably unravel. That was baked into it from the beginning.

And it was funny, because when we put our first record out, people would say, “Wow, this is so uplifting, so positive!” And I’d be thinking: Did you read the lyrics? Because underneath that rejoicing is something way more fragile. The voices are of people who feel alienated, but who have just discovered this new kind of freedom—and they’re holding onto it like it might slip away at any moment.

Which, of course, it will.

Was that when you formed Ages and Ages—right in the middle of that moment of optimism?

Yeah, that was pretty much the moment. That feeling—that kind of almost reckless optimism—was exactly where Ages and Ages came from.